For help and expert advice:

1 877 260 39501 877 260 3950

For help and expert advice:

1 877 260 39501 877 260 3950

A history of the Kingdom of Jordan, from ancient times to modern day.

The recorded history of Trans-Jordan (the historic name for Jordan) revolves mostly around the fertile north and west of the country, with the history of the sparsely populated arid south and east surviving only through the oral traditions and culture of the nomadic Bedouins.

Evidence of human settlement in Trans-Jordan dates back to the Palaeolithic period (500000-17000 BC). No direct architectural evidence from this era exists, but archaeologists have found tools, such as flint and basalt hand-axes, knives and scraping implements.

In the Neolithic period (8500-4500 BC), three major shifts occurred. Firstly, people became sedentary living in small villages and at the same time, new food sources were discovered and domesticated, such as cereal grains, peas and lentils, as well as goats. The population increased reaching tens of thousands of people.

Second, the shift in settlement patterns was brought about by a marked change in the weather, particularly the eastern desert, which grew warmer and drier, eventually becoming entirely uninhabitable for most of year. This watershed climate change is thought to have occurred between 6500 and 5500 BC.

Third, between 5500-4500 BC pottery from clay began to be produced, replacing the existing plaster pottery. These new pottery techniques were likely introduced to the area by craftsmen from Mesopotamia.

During the Chalcolithic period (4500-3200 BC) copper was first smelted and used to make axes, arrowheads and hooks. Cultivation of barley, dates, olives and lentils, and the domestication of sheep and goats predominated over hunting. In the desert, the lifestyle was probably similar to that of modern Bedouins.

During the Early Bronze Age (3200-1950 BC), villages began to included defensive fortifications, probably to protect against marauding nomadic tribes. Simple water infrastructures were also constructed. Trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia brought with it the development of writing in Trans-Jordan, Palestine and Syria.

Between 2300-1950 BC, many of the large, fortified hilltop towns were abandoned in favour of either small, unfortified villages or a pastoral lifestyle. The reason for this shift is unknown, though it is thought to be combination of climactic and political changes.

During the Middle Bronze Age (1950-1550 BC), migration in the Middle East increased and trading continued to develop between Egypt, Syria, Arabia, Palestine and Trans-Jordan, which resulted in the spread of civilization and technology. Bronze forged from copper and tin allowed for the production of more durable tools and weapons. Large and distinct communities appeared in northern and central Trans-Jordan, while the south was populated by nomadic Bedouins.

New fortifications appeared at sites like Amman's Citadel, Irbid, and Tabaqat Fahl (or Pella). Towns were surrounded by ramparts made of earth embankments and the slopes were covered in hard plaster, making it slippery and difficult to climb. Pella was enclosed by massive walls and watch towers.

Towards the end of the Bronze Age many of the near Eastern and Mediterranean kingdoms collapsed. The main cities of Mycenaean Greece and Cyprus, the Hittites in Anatolia, and Syria, Palestine and Jordan were all destroyed. It is believed that this destruction was brought about by the "Sea Peoples" marauders from the Aegean and Anatolia, one group of which was the Philistines, who settled on the southern coast of Palestine and gave the area its name. The Sea Peoples were eventually defeated by the Egyptian pharaohs Merenptah and Rameses III.

The Israelites may have been another cause of the late Bronze Age devastation in Palestine. Although the archaeological record is unclear it is certain that the Israelites destroyed many Canaanite towns including Ariha (Jericho), Ai and Hazor.

The Iron Age (c. 1200-332 BC) saw the development of three new kingdoms in Jordan: Edom in the south, Moab in central Jordan, and Ammon in the northern mountain areas. To the north in Syria, the Aramaeans made their capital in Damascus. This period saw a shift in the power from individual 'city-states' to larger kingdoms. One possible reason for this was the growth of the trade routes from Arabia, which brought gold, spices and precious metals via Amman and Damascus to northern Syria.

Most of the Biblical Old Testament took place during this period, but there is little archaeological evidence to fully support the Biblical account of the Israelites’ occupation of Palestine.

According to the Biblical account of the Exodus from Egypt (c. 1270-1240 BC), the Israelite tribes trekked north, and through a combination of alliances and war eventually crossed the Jordan River into Palestine. A united Kingdom of Israel arose there about 1000 BC with Saul and David as its first kings. After the death of David's son King Solomon in 922 BC, the kingdom was divided into two, with Israel to the north and Judah to the south.

Although Egypt still nominally ruled the lands of Jordan and Palestine, attacks from the “Sea Peoples' of the Mediterranean Sea had weakened the Paranoiac Empire and allowed the Philistines to gain a foothold in Palestine and Jordan. The Philistines skills in weapon-making gave them a greater military advantage and helped in their early victories over the Israelite tribes. By around 1000 BC, however, iron was in widespread use throughout the region.

This trouble for the Israelites was good for the kingdoms of Jordan. The split into Israel and Judah in 922 BC, and an invasion of the Egyptians against Israel four years later, gave the three kingdoms of Jordan time to prosper.

The Edomites occupied southern Jordan with their capital at Buseira. They were skilled in copper mining and smelting, and had settlements near modern-day Petra and Aqaba. The Kingdom of Moab covered the centre of Jordan, and its capital cities were at Karak and Dhiban. The Kingdom of Ammon around 950 BC displayed increasing prosperity based on agriculture and trade, as well as an organized defence with a series of fortresses. Its capital was in the Citadel of present-day Amman.

The wealth of these kingdoms made them targets for raids and in particular by the Assyrians with their capital at Ashur in northern Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). Although the Assyrians managed to capture Damascus and Samaria, the capital of the northern kingdom of Israel, the kingdoms of Ammon, Moab and Edom retained their independence by buying the Assyrians off with tributes.

The Assyrian Empire came to a sudden end in 612 BC, when Nineveh fell to an alliance of Persia and Babylonia. In its place arose the Babylonian Empire and King Nebuchadnezzar, whose defeat of the Egyptians at Carchemish in 605 BC threw much of the region into turmoil.

In 539 BC, the Persians under Cyrus II brought to an end the disruptive rule of the Babylonian Empire and made way for a period of more organized life and prosperity. The Persian Empire became the largest yet known in the Near East, and Cyrus' successors conquered Egypt, northern India, Asia Minor, and were frequently in conflict with the Greek states of Sparta and Athens. Internal turmoil continued in Jordan, with numerous clashes occurring between the Moabites and Ammonites and against the Jews of Palestine.

After establishing the greatest empire yet seen in the Near East, economic decline, revolts, murders and palace intrigue weakened the Persian throne. In 332 BC, Alexander the Great sacked the Persian capital of Persepolis (in modern Iran) and established Greek control over Jordan and surrounding countries.

Alexander the Great’s conquest of the Middle East and Central Asia firmly consolidated the influence of Hellenistic culture. The Greeks founded new cities in Jordan, such as Umm Qais (known as Gadara) and renamed others, such as Amman (renamed from Rabbath-Ammon to Philadelphia) and Jerash (renamed from Garshu to Antioch, and later to Gerasa). Many of the sites built during this period were later changed during the Roman, Byzantine and Islamic eras, so only fragments remain from the Hellenistic period. The most spectacular Hellenistic site in Jordan is the Qasr al-Abd ('Castle of the Slave') at ‘Iraq al-Amir, just west of modern-day Amman. Greek was established as the official language, although Aramaic remained the primary spoken language of ordinary people.

Alexander died soon after establishing his empire, and his generals subsequently fought over control of the Near East for more than two decades. Eventually, the Ptolemies secured power in Egypt and ruled Jordan from 301-198 BC. The Seleucids, who were based in Syria, ruled Jordan from 198-63 BC.

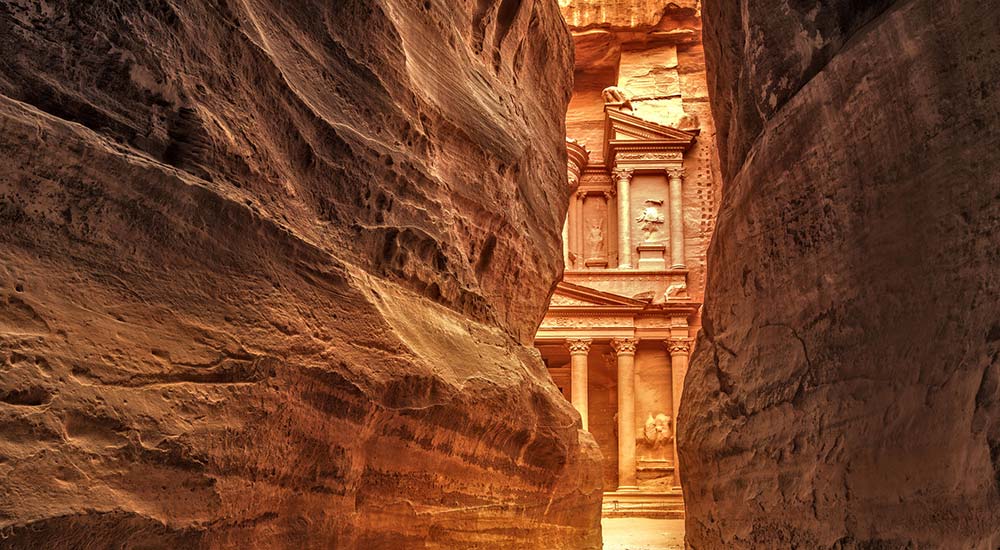

Before Alexander’s conquest, a new civilization had emerged in southern Jordan. The Nabateans, a nomadic tribe, began migrating gradually from Arabia during the sixth century BC. Over time, they abandoned their nomadic ways and settled in a number of places in southern Jordan, the Naqab desert in Palestine, and in northern Arabia. Their capital city was the legendary rock-hewn city of Petra, Jordan's most famous tourist attraction.

The Nabateans were skilled traders and facilitated commerce between China, India, the Far East, Egypt, Syria, Greece and Rome. They dealt in spices, incense, gold, animals, iron, copper, sugar, medicines, ivory, perfumes, fabrics and many others. From its origins as a fortress city, Petra became a wealthy commercial crossroads between the Arabian, Assyrian, Egyptian, Greek and Roman cultures. Control of this important trade route between the upland areas of Jordan, the Red Sea, Damascus and southern Arabia was the lifeblood of the Nabatean Empire.

Little is know about Nabatean society; however scant records show their community was governed by a royal family, although a strong spirit of democracy existed. There were no slaves in Nabatean society, and all members shared in work duties. The Nabateans worshipped a pantheon of deities, chief among which were the sun god Dushara and the goddess Allat.

As the Nabateans grew in power and wealth, they attracted the attention of their neighbours. In 312 BC the Seleucid King Antigonus sacked Petra only to be destroyed by the Nabateans in the desert on his return journey north, whilst over-laden with booty. Throughout much of the third century BC, the Ptolemies and Seleucids warred over control of Jordan, with the Seleucids emerging victorious in 198 BC. Nabatea remained largely untouched and independent throughout this period.

Although the Nabateans resisted military conquest, the Hellenistic culture of their neighbours influenced them greatly. Hellenistic influences can be seen in Nabatean art and architecture, especially during the time that their empire was expanding northward into Syria, around 150 BC. In 65 BC, the Romans arrived in Damascus and two years later, Pompey dispatched a force to subdue the Nabateans

The assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BC led to a period of relative insatiability for the Romans in Jordan. The Parthian kings of Persia and Mesopotamia took this opportunity to invade and the Nabateans made the mistake by siding with them. After the Parthians' defeat the Nabatean Kingdom gradually fell under Roman control and in 106 AD they claimed it completely and renamed it Arabia Petrea. The city of Petra was redesigned according to traditional Roman architectural designs, and a period of relative prosperity ensued under the Pax Romana.

At its height, under Roman rule, Petra may have grown to house 20,000-30,000 people. However, with a shift of trade routes to Palmyra in Syria and the expansion of seaborne trade around the Arabian Peninsula, their fortunes declined until sometime during the fourth century AD, the Nabateans left their capital at Petra.

Pompey's conquest of Jordan, Syria and Palestine in 63 BC began a period of Roman control which would last four centuries. In northern Jordan, the Greek cities of Philadelphia (Amman), Gerasa (Jerash), Gadara (Umm Qais), Pella and Arbila (Irbid) joined with other cities in Palestine and southern Syria to form the Decapolis League, a fabled confederation linked by economic and cultural interests.

Of these, Jerash appears to have been the most splendid. It was one of the greatest provincial cities in Rome's empire, and was honoured by a visit from the Emperor Hadrian himself in 130 AD. In 111 AD the Via Nova Triana (Trajan New Road) was completed, which ran from the southern port of Aqaba all the way to the Syrian city of Bosra. Forts and watch-towers were built along this and other trade routes, while Amman, Jerash, and Umm Qais were laid out with colonnaded streets and theatres. It was generally a peaceful period during which the Greek influences of language and culture were gradually replaced with Roman culture.

The Byzantine period dates from the year 324 AD, when the Emperor Constantine I founded Constantinople (Istanbul) as the capital of the Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, Empire. Constantine converted to Christianity in 333 AD. In Jordan, however, the Christian community had developed much earlier and Pella had been an important centre of refuge for Christians fleeing persecution in Rome during the first century AD.

During the Byzantine period all of the major cities of the Roman era continued to flourish, and the regional population boomed. Christianity gradually became the accepted religion of the area in the fourth century and churches and chapels began to sprout up across Jordan. Church-building underwent extraordinary growth during the reign of Emperor Justinian (527-65).

In the sixth and seventh centuries, Jordan suffered severe depopulation. The plague of 542 wiped out much of the population and the short lived Persian Sassanian invasion of 614 led to the occupation of Jordan, Palestine and Syria for some fifteen years. The Byzantine Emperor Heraclius managed to recover the area in 629, but these gains were not to last for long.

For countless years marauding Bedouin tribesmen from the Arabian Desert had periodically staged raids to the north. However, the Arabs who now swept northward on horse and camel-back were united by a common faith, that of Islam

It took the Arabs only ten years to dismantle Byzantine control over the lands of Jordan, Palestine and Syria. After two unsuccessful attacks against the Byzantine garrison town of Mu'ta (south of Amman, near Karak) in 629, the Muslim Arab tribes regrouped for a much wider military campaign. In the 636, the Muslim armies overran the Trans-Jordanian highlands and won a decisive battle against the Byzantines on the banks of the Yarmouk River, which marks the modern border between Jordan and Syria. This victory opened the way to the conquest of Syria, and the remaining Byzantine troops were forced back into Anatolia only a few years later.

The Muslims soon took Damascus, and in 661 proclaimed it the capital of the Umayyad Empire. Jordan prospered during the Umayyad rule (661-750) due to its proximity to the capital city of Damascus. As Islam spread, the Arabic language gradually came to dominate, though Christianity was still widely practiced throughout the 9th century.

They constructed caravan stops (caravanserais), bath houses, hunting complexes and palaces in the eastern Jordanian desert. These palaces are collectively known as the 'Desert Castles.' Examples of Umayyad architecture include the triple-domed Qusayr 'Amra bath house with its magnificent frescoed walls, and the massive Qasr al-Haraneh. The greatest of all Umayyad constructions is the Dome of the Rock Mosque, built by Caliph 'Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan in 691, in al-Quds (Jerusalem).

In 750 the Umayyads were defeated by the Abbasids, who established their capital in Baghdad, leaving Jordan a provincial backwater far from the centre of the empire. The Desert Castles were abandoned, and Jordan now suffered more from neglect than from the ravages of invading armies. However, recent excavations have shown that the population of Jordan continued to increase, at least until the beginning of the 9th century.

In 969, the Fatimids of Egypt took control of Jordan and struggled over it with various Syrian factions for about two centuries. In 1095 the Emperor of Constantinople, Alexius, made a plea for help to his Christian European brothers that his city, and last bastion of Byzantine Christendom, was under imminent threat of attack by the Muslim Turks. Pope Urban II was able to muster support for Constantinople as well as for the retaking of Jerusalem and so started the legendary Crusades.

The so-called 'Holy Wars' thus began in 1096. They resulted in the conquest of al-Quds (Jerusalem) by Christian forces and the establishment of a kingdom there. In an attempt to protect the route to Jerusalem, Crusader King Baldwin I built a line of fortresses down the backbone of Jordan. The largest of these were at Karak and Shobak. However, after having unified Syria and Egypt under his control, the Muslim commander Salah Eddin al-Ayyubi (Saladin) defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of Hittin in 1187. This opened the way for the Muslim armies to recapture Jerusalem, effectively eliminating the foreign domination of Jordan.

Salah Eddin founded the Ayyubid dynasty, which ruled much of Syria, Egypt and Jordan for the next eighty years. In 1258, an invasion of Mongols swept across much of the Near East. The marauding invaders were eventually defeated in 1260 by the Mamluk Sultan Baybars, at the battle of Ein Jalut. The Mamluks, who originated from Central Asia and the Caucasus, grasped power and ruled Egypt, and later Jordan and Syria, from their capital at Cairo.

The unification of Syria, Egypt and Jordan under the Ayyubids and Mamluks led to another period of stability and prosperity for Jordan. Castles were constructed or rebuilt, and caravanserais were set up to host pilgrims and strengthen lines of communication and trade. Sugar was produced and refined at water-driven mills in the Jordan Valley. Another Mongol invasion in 1401, along with weak government and widespread disease, led to the Mamluks defeat by the Ottoman Turks in 1516. Jordan thus became part of the Ottoman Empire and remained so for the next 400 years.

The four centuries of Ottoman rule (1516-1918) were marked by a general stagnation in Jordan. The Ottomans were only interested in Jordan's significant position on the pilgrimage route to Mecca. They built a series of fortresses to protect pilgrims from the desert tribes and to provide them with sources of food and water. However, the Ottoman administration was weak and many towns and villages were abandoned, agriculture declined, and families and tribes moved frequently from one village to another. Population continued to dwindle until the late 19th century, when Jordan received several waves of immigrants from Syria and Palestine, and from Muslim Circassians and Chechens further to the north.

The most significant infrastructural development of the Ottoman period was the Hijaz Railway from Damascus to al-Madina al-Munawarra in 1908. Designed originally to transport pilgrims to Mecca al-Mukarrama - the extension from al-Madina al-Munawwara was never completed - the railway was also useful for ferrying Ottoman armies and supplies into the Arabian heartland. Because of this, it was attacked frequently during the Great Arab Revolt of World War I.

Much of the trauma and dislocation suffered by the peoples of the Middle East during the 20th century can be traced to the events surrounding World War I. During the conflict, the Ottoman Empire sided with the Central Powers against the Allies. Seeing an opportunity to liberate Arab lands from growing Turkish oppression and discrimination, and trusting the honour of British officials who promised their support for a unified kingdom for the Arab lands, Sharif Hussein bin Ali, Emir of Mecca and King of the Arabs (and great grandfather of King Hussein), launched the Great Arab Revolt.

In June 1916, as head of the Arab nationalists and in alliance with Britain and France, Sharif Hussein started the Great Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule. His sons, the emirs Abdullah and Faisal, led the Arab forces, with Emir Faisal's forces liberating Damascus from Ottoman rule in 1918. At the end of the war, Arab forces controlled all of modern Jordan, most of the Arabian Peninsula and much of southern Syria. However, the European victors reneged on their promises to the Arabs, carving from the dismembered Ottoman lands a patchwork system of mandates and protectorates. The Hashemite family was only able to secure Arab rule over Trans-Jordan, Iraq and Arabia.

When King Abdullah I was first installed, the country didn't look the way it now does. Trans-Jordan first took Aqaba from al-Hijaz, and then expanded its boundary exchange with Saudi Arabia to give up a considerable area of desert and get closer to Aqaba.

At the end of World War I, the territory now comprising Israel, Jordan, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, and Jerusalem was awarded to the United Kingdom by the League of Nations as the mandate called "Palestine Trans-Jordan." In 1922, the British, with the League's approval under the terms of the Mandate, partitioned Palestine at the Jordan River and established the semi-autonomous Emirate of Trans-Jordan in those territories to the east. The British installed the Hashemite Prince Abdullah I while continuing the administration of separate Palestine and Trans-Jordan under a common British High Commissioner. The mandate over Trans-Jordan ended on May 22, 1946; on May 25, the country became the independent Hashemite Kingdom of Trans-Jordan. It ended its special defence treaty relationship with the United Kingdom in 1957.

Trans-Jordan was one of the Arab states opposed to the second partition of Palestine and creation of Israel in May 1948. It participated in the war between the Arab states and the newly founded State of Israel. The Armistice Agreements of April 3, 1949 left Jordan in control of the West Bank and provided that the armistice demarcation lines were without prejudice to future territorial settlements or boundary lines.

In March of 1949, Trans-Jordan became Jordan, and annexed the West Bank. Only two countries however recognized this annexation: Britain and Pakistan. It is unknown why Pakistan recognized this annexation.

In 1950, the country was renamed "the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan" to include those portions of Palestine annexed by King Abdullah. While recognizing Jordanian administration over the West Bank, the United States, other Western powers and the United Nations maintained the position that ultimate sovereignty was subject to future agreement. After the assassination of King Abdullah I in 1951, his son Tala was crown King but less than a year later was forced to abdicate because of a poor mental condition. His son Crown Prince Hussein was proclaimed King of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan on August 11, 1952, at the age of 16.

In February 1958, following announcement of the merger of Syria and Egypt into the United Arab Republic, Iraq and Jordan announced the Arab Federation of Iraq and Jordan, also known as the Arab Union. The Union was dissolved in August 1958.

Jordan signed a mutual defence pact in May 1967 with Egypt, and it participated in the June 1967 war between Israel and the Arab states of Syria, Egypt, and Iraq. During the war, Israel gained control of the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

The 1967 war led to a dramatic increase in the number of Palestinians living in Jordan. Its Palestinian refugee population - 700,000 in 1966 - grew by another 300,000 from the West Bank. The period following the 1967 war saw an upsurge in the power and importance of Palestinian militants (fedayeen) in Jordan. The heavily armed fedayeen constituted a growing threat to the sovereignty and security of the Hashemite state, and open fighting erupted in June 1970.

Other Arab governments attempted to work out a peaceful solution, but by “Black” September, continuing fedayeen actions in Jordan - including the destruction of three international airliners hijacked and held in the desert east of Amman - prompted the government to take action to regain control over its territory and population. In the ensuing heavy fighting, a Syrian tank force took up positions in northern Jordan to support the fedayeen but was forced to retreat. By September 22, Arab foreign ministers meeting at Cairo had arranged a cease-fire beginning the following day. Sporadic violence continued, however, until Jordanian forces won a decisive victory over the fedayeen in July 1971, expelling them from the country.

No fighting occurred along the 1967 Jordan River cease-fire line during the October 1973 Arab-Israeli war, but Jordan sent a brigade to Syria to fight Israeli units on Syrian territory.

In 1988, Jordan renounced all claims to the West Bank but retained an administrative role pending a final settlement, and its 1994 treaty with Israel allowed for a continuing Jordanian role in Muslim holy places in Jerusalem.

Jordan did not participate in the Gulf War of 1990-1991. The war led to a repeal of U.S. aid to Jordan due to King Hussein’s support of Saddam Hussein.

In 1991, Jordan agreed, along with Syria, Lebanon, and Palestinian representatives, to participate in direct peace negotiations with Israel sponsored by the U.S. and Russia. It negotiated an end to hostilities with Israel and signed a declaration to that effect on July 25, 1994. As a result, an Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty was concluded on October 26, 1994. Following the outbreak of Israeli-Palestinian fighting in September 2000, the Jordanian government offered its help to both parties. Jordan has since sought to remain at peace with all of its neighbours.

In Jan. 1999, King Hussein unexpectedly deposed his brother, Prince Hassan, who had been heir apparent for 34 years, and named his eldest son as the new crown prince. A month later, King Hussein died of cancer, and Abdullah, 37, a popular military leader with little political experience, became king.

The first parliamentary elections under King Abdullah took place in June 2003 and resulted in a two-thirds majority for the king's supporters. In 2005, the king, unhappy with the slow progress on reforms, replaced his cabinet.